BERLIN – The small town that started as little more than a tavern at a crossroads marks its 150th anniversary in 2018.

In spite of three devastating fires, the decline of the railroad and the rise and fall of countless businesses through the decades, Berlin has endured. Today, the town pays homage to its history with a focus on maintaining the small-town charm it’s become known for while promoting 21st century living.

The municipality will celebrate the 150th anniversary of its incorporation with a ceremony Saturday during Oktoberfest. Though much has changed in the past century and a half, what makes Berlin unique has not.

“It’s the community spirit of the people in Berlin,” said Hale Harrison, who grew up in Berlin as his family operated the renowned Harrisons’ Nurseries. “Whether they’ve been there a year or 40 years, they all jump in to help.”

According to historians, though Berlin wasn’t incorporated until 1868, settlement in the area began with a 300-acre land grant dating back to 1677. That land, known as the Burley tract, was one of four land grants that make up what is now considered Berlin.

In 1779, naval hero Stephen Decatur was born in Berlin. His parents, residents of Philadelphia, traveled to Worcester County as British troops occupied their city. Decatur was born in an unpretentious house that was located in what is now the Decatur Farms community. Though he lived in town for just a few months after his birth, a monument in his honor remains at Stephen Decatur Park today.

By the 1790s, a small village had formed in what is now Berlin. One of those early homes, the Stevenson House, is still on Main Street today. The area gradually became known as Berlin, purportedly as travelers began to shorten the name of the village’s “Burleigh Inn.”

As years went by the town’s landscape was filled in with several other notable homes, including Robin’s Nest on West Street, Burley Cottage and Burley Manor on South Main Street and the Pitts House on William Street. Robin’s Nest, initially known as the Whaley House, was built around 1805 and was mortgaged in 1823 for $1,596 according to “Along the Seaward Side,” Paul Baker Touart’s architectural history of Worcester County. The book details the history of a variety of Berlin landmarks, including Burley Manor, which has been tied to the Hammond family since the 1830s.

“Burley Manor today is a veritable view of what a working manor farmstead looked like,” said Berlin native and local historian Joe Moore. Moore credits Burley Manor’s Ed Hammond, who died in 2011, with bringing about the restoration of several key buildings in Berlin, including the Calvin B. Taylor House Museum.

“Ed was an avid preserver of historic buildings,” said Moore, a longtime friend. “At one time he owned an interest in five buildings.”

Calvin B. Taylor, whose home is now the museum, was born in Berlin in 1857. He is revered today for his efforts as an educator, lawyer, banker and politician. It was in 1907 that he incorporated the Calvin B. Taylor Banking Company of Berlin. In the 1980s, Taylor’s home was purchased by the town and restored, now offering visitors a glimpse at the town’s diverse history.

It was Taylor who reportedly taught the Rev. Dr. Charles Albert Tindley, a minister and distinguished gospel music composer who hailed from Berlin, to read in the latter half of the 19th century.

Another notable early Berlin home still in existence today is Windy Brow, the lone reminder of the lucrative nursery business that was once the county’s largest employer. The iconic home on Harrison Avenue was built in 1899 by Orlando Harrison, whose father launched Harrisons’ Nurseries in Berlin in the 1880s. The elder Harrison, previously a strawberry grower in Sussex County, purchased a farm in Berlin, near where Stephen Decatur High School now sits. The family wasted no time in nurturing the neglected peach trees on the property and quickly planted 2,000 more. An 1897 brochure from Harrison’s Nurseries states that the business at that time boasted 1.5 million peach trees, 10 million strawberry plants and 500,000 asparagus roots.

“It grew to be a very large operation very quickly,” said Hale Harrison, grandson of Orlando Harrison. “It was at one time the largest grower of fruit trees in America.”

He said the business had 5,000 acres in the greater Berlin area. Moore pointed out that Harrison Avenue had been created because the town’s mayor at the time had asked Orlando Harrison to keep the big trucks visiting the nursery off Main Street.

“Harrisons’ Nurseries was the largest employer in town but also a foundation of Berlin in regard to the economic benefits to the town,” Moore said.

Harrisons’ Nurseries was such a large business that during World War II, Germans at a prisoner of war camp in Somerset County were transferred to Worcester County to work for the company. According to Moore, a satellite camp was set up east of Seahawk Road and at least half of the soldiers there were sent to work at Harrisons’ Nurseries.

Orlando Harrison, known for his role in growing the nursery business, went on to serve as Berlin’s mayor in the beginning of the 20th century. During his time in office, the town launched municipally owned water and light systems. He went on to serve in the Maryland Senate in the 1920s.

Harrisons’ Nurseries operated until 1962.

“What brought about the end,” Hale Harrison said, “was the increase in refrigerated railroad cars and refrigerated trucks. Then peaches could be grown further south and still make it to market.”

The railroad through town, which had been used heavily by Harrisons’ Nurseries, also slowed in those years. The train station, between Windy Brow and Main Street, closed in the middle of the 20th century.

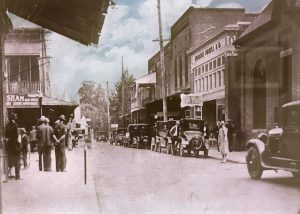

While Berlin is still home to many of the 19th century houses detailed in local historical texts, the majority of the downtown business district dates back to the early 1900s, as devastating fires in 1895, 1901 and 1904 destroyed much of Berlin. After the first fire, town officials began requiring that burned businesses be rebuilt with brick. According to “Worcester County Maryland’s Arcadia,” conflagrations included a livery stable fire in 1895 and a fire near the Odd Fellows Building in 1901.

“In 1904 fire broke out again, this time in the Berlin Veneer Works on the west side and, fanned by near gale winds, swept through the heart of town,” the book reads. “It destroyed a major mill and lumber yard, residences up to and across West Street to obliterate the Tingle Place and a number of homes on both sides of Washington Street, together with Buckingham Presbyterian and St. Paul’s Episcopal Churches. In view of the limitation in both water supply and fire-fighting equipment, it was barely short of a miracle that the entire town was not decimated repeatedly.”

Though Buckingham Presbyterian Church was completely destroyed, the church as it appears today was rebuilt in 1905. St. Paul’s, which was established in 1825, fared somewhat better and was reconstructed in 1905 with its original brick walls. Stevenson United Methodist Church, and St. Paul United Methodist Church, both of which trace their roots back to the 19th century, were built in 1912 and 1915 respectively.

The Berlin Fire Company was formed in the wake of the town’s tragic trio of fires, boasting 26 volunteers in 1910. At that time, it was located near where town hall is now.

The star of the town’s downtown, the Atlantic Hotel, dates back to 1895. Though a hotel was on the site as early as the mid-19th century, the hotel as we know it now was constructed after the August 1895 fire. Though it was a centerpiece for the town for decades, the hotel and the town around it declined during the Great Depression and into the middle of the 20th century as Ocean City’s popularity grew. As storefronts were tacked onto the front of the hotel it gradually fell into disrepair.

“As commercial practices changed, and the automobile became the choice mode of transportation, the hotel went into a decline,” reads the “Images of America, Berlin” book. “The dining room closed. Next, like the rest of downtown, the stores inside began to suffer and became marginal. The hotel hiding behind the brick and Formstone became a flophouse. Something had to be done. Ten native couples resolved to change things at the hotel and were determined to restore it. With only a hope and a prayer and no thought or motive of profit, they bought it.”

Hale Harrison and Joe Moore, who were both born in Berlin, are pictured looking through historical postcards during an interview this week. Photo by Charlene Sharpe

Moore, who served as the Town of Berlin’s attorney from 1975 to 1989, remembers the period well. Though longtime businesses Style Guide and Farlow’s Pharmacy were still in town, many storefronts were empty.

“Everything moved to Ocean City,” he said, pointing out that he too had purchased an office in the resort town to serve clients there. “The Atlantic Hotel, it came very close to being razed.”

Moore recalls learning as town attorney that a potential purchaser for the property had come forward with plans to demolish it. He said John Howard Burbage, the mayor at that time, helped prevent that from happening. It was then that the 10 local investors came up with the plan to purchase it. Original investors included: Ed Hammond, James and Nancy Barrett, Charles Jenkins Sr., Reese Cropper Jr., William and Anna Esham, William and Gloria Esham, Richard and Cheryl Holland, William and Susan Mariner, Clark and Jeanne Hamilton and Elizabeth Henry Hall. Hall died before the restoration was complete and her share was taken over by Alan Guerrieri.

“They did it to save the hotel,” Moore said.

In a 2015 interview, Cropper said Hammond and Barrett had approached him and asked whether he’d be interested in a business deal that likely wouldn’t make him any money but would be a source of pleasure.

“It was true what they promised,” he said. “This partnership is so unique because no one got into it expecting to get anything back.”

Local contractor Larry Widgeon was hired to restore the building in 1986.

“When restoration started, the building was in such poor condition that one could stand on the first floor and see the sky through the third-floor roof,” reads the “Images of America, Berlin” book. “Three inches of water stood in the dining room. The brick walls bulged. Larry commenced tearing out; the partners wrung their hands. Larry tore more; the partners wrung harder. Finally, however, he started putting back.”

In 1992, the restoration was complete and the addition of a gourmet chef made the hotel a true attraction.

“People would come from everywhere to go to the Atlantic Hotel,” Moore said.

It wasn’t long after that Berlin drew the notice of Hollywood director Garry Marshall. In 1998 Berlin was transformed into fictional Hale, Md., for the filming of Runaway Bride, starring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts. In 2001, Berlin underwent an even greater transformation as streets were covered with dirt and horses and carriages were brought in for the filming of Tuck Everlasting, starring Sissy Spacek, William Hurt and Ben Kingsley.

In the years following the movies, the town truly became a tourist destination. Moore remembers the day his wife called him to say she’d seen a tour bus on Main Street.

“That was unheard of,” Moore said.

And while the town has changed tremendously in recent decades, longtime residents love it just as much as they always have. Carol Rose, who grew up in the house her grandfather built on William Street, can’t help but compare the town, particularly during her childhood, to Andy Griffith’s Mayberry.

“If you did something you weren’t supposed to your mother knew about it before you got home,” she said.

Rose, whose father ran a filling station located where the J&M Meat Market is now, recalls shopping for penny candy downtown and having new wheels put on her roller skates at Williams Five-and-Dime. Each December, the second-floor storage space of the shop was transformed into Santa’s workshop, strung with holiday lights and filled with table after table of all the latest children’s toys.

Rose’s first summer job was at the Dairy Queen, which was in the space now occupied by Island Creamery.

“We made the ice cream sandwiches ourselves,” Rose said.

Washington Street resident Helen Hannaway remembers moving to Berlin from Parksley, Virginia, in 1948 as a teenager.

“There was a great crowd of kids we ran around with,” she said. “There was a soda fountain on every block in those days. We haunted those little places.”

As she went on to marry and have children, Hannaway’s appreciation of the quiet town grew.

“My kids have always said they’re so thankful they grew up in this town in the era they did,” she said. “Everybody knew you and there wasn’t any crime to speak of.”

Rose has a similar appreciation of Berlin. While much has changed during her lifetime—she remembers when the library was in town hall and when ballroom dancing lessons were offered in the Eschenburg house—the town continues to value its history, something that she believes makes it special. Rose, who has served on the town’s historic district commission for a dozen years, is grateful for property owners like locals Ernest Gerardi and Michael Queen who have purchased old buildings and restored them.

“The people that have these buildings take pride in them,” she said.

While visitors these days come to town to shop and dine, Rose believes they also come to simply soak up the historic ambience of Berlin.

“It’s just a beautiful place,” she said. “I love it.”

Mayor Gee Williams says he believes the town’s 150th anniversary is an opportunity to reflect upon its success. He will make a speech at 2 p.m. Saturday on Artisans Green to mark the event.

“I just think the 150th anniversary is a great opportunity to reflect on our past and be grateful for what we’ve achieved and to look forward with optimism to the opportunity to create a better Berlin in the next 150 years,” Williams said. “We have always been a community that’s adapted to change. It’s not always easy but by adapting, our community’s gotten stronger, more vibrant, and more embracing of people of all backgrounds. We seem to share a common vision of what quality of life means in a small town.”

Williams, who like many was born and raised in Berlin, said the time he spent away from the Eastern Shore as he attended college and served in the U.S. Army Reserves taught him something.

“That has made me more appreciative of what we have here,” he said. “I like to think the overwhelming majority of people instinctively understand that just because you live in a small town doesn’t mean you have to live in a small world.”