OCEAN CITY – While it remains to be seen if a proposed federal rule change to reduce offshore speed limits for recreational and commercial vessels comes to fruition, the Biden administration this week denied a petition to institute the changes immediately.

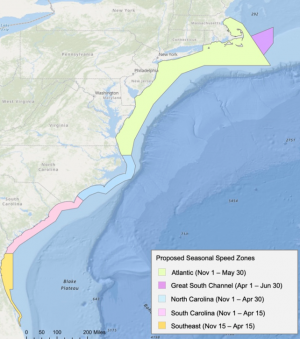

In an effort to save endangered North Atlantic right whales, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has proposed a 10-knot speed restriction for recreational and commercial vessels 35 feet in length or greater, down from the current 65 feet. The proposed rule change would expand the go-slow zones to include virtually the entire east coast out to a 90-mile radius and extend the zone restrictions to as many as seven months of the year.

NOAA has yet to make a final decision on the proposed rule change, but national environmental advocacy group Oceana and other conservation groups in December filed an emergency rulemaking petition seeking an immediate implementation of the proposed 10-knot rule. However, this week the Biden administration, through the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) denied the emergency petition to immediately implement the proposed 10-knot rule change.

The denial does not necessarily mean the proposed rule change is dead. Instead, NMFS officials have reportedly said the agency does not have the resources to effectively implement emergency regulations while the decision on the longer-term rule change is still being explored. Instead, NMFS officials have said the agency continues to work with vessel operators to get voluntary slowdowns, at least while the right whale calving season is in full swing.

Right whales begin giving birth to calves around mid-November until mid-April and their calving grounds are typically in the warm water off the Atlantic coast from North Carolina to Florida, although they migrate through the mid-Atlantic area on their way to the calving grounds. Pregnant females and mothers with nursing calves are particularly vulnerable to vessel strikes because they much of their time near the surface of the water, according to published reports.

There are currently only about 340 right whales in existence, a number that has steadily declined in recent years. The population is down to about 70 reproductive females, according to published reports.

“Instead of doing what is necessary to protect North Atlantic right whales, NMFS is turning its back on this critically endangered species,” said Oceana Campaign Director Gib Brogan. “Their refusal to take immediate action continues the agency’s history of delays and leaves new mothers and calves in danger. These whales are particularly vulnerable to boat strikes because they spend their time at the water’s surface. In just that last week, half a dozen right whale sightings have occurred outside of existing protection areas and none of the whales in the southeast region are protected from smaller boats that can and do kill right whales. The government’s own assessment clearly shows that more needs to be done for this species to reduce the risk of whale mortality.”

The Center for Biological Diversity took it a step further in criticizing the president’s administration for failing to take appropriate emergency action.

“I’m outraged that the Biden administration won’t shield these incredibly endangered whales from lethal ship strikes,” said Center for Biological Diversity Oceans Program Legal Director Kristen Monsell. “This is an extinction-level emergency. Every mother right whale and calf is critical to the survival of the species. Protecting right whales from vessel strikes is even more crucial after the Senate’s recent omnibus bill, which delayed efforts to curb right whale entanglements in lobster gear.”

The proposed rule change could severely damage the local fishing industry. While the proposed rule change would only be in effect from Nov. 1 to May 31, which is just on the shoulders of the recreational fishing season locally, the 10-knot rule could be applied at any time by NOAA if a right whale was spotted in the fishing grounds off the coast.

The local fishing community, along with fishing advocacy groups up and down the east coast, from the beginning have railed against the proposed 10-knot rule change. While all agree protecting the endangered species is important, there is limited data suggesting vessel strikes are contributing to mortality rates for the species. For example, according to NOAA’s own data, there have only been 12 lethal right whale vessel strikes since 2008, five of which have come from vessel’s under 35 feet. From NOAA’s own data, the chance of a vessel striking a right whale, considering the sheer volume of boat traffic in the prescribed zones for the rule change, is about one in a million.

Nearly all the local fishing grounds frequented by recreational and commercial fishermen would fall under the 10-knot rule. Operating a vessel at a maximum of 10 knots would add several hours to a typical charter or private fishing trip.

Charters targeting billfish, tuna and mahi, for example, often chug nearly 100 miles to reach the canyons offshore and leave well before sunrise and return in the evening. It’s often a three-hour-plus ride to reach the offshore canyons without any 10-knot maximum speed in place. To put it in perspective, one knot is equal to around 1.15 mph. A 100-mile trip to the canyons offshore would take two or three times longer than usual under normal circumstances.