(Editor’s Note: The following is another installment of an ongoing series during Black History Month.)

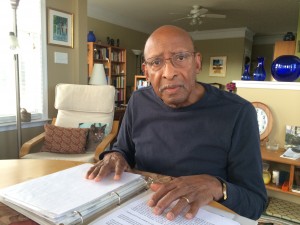

BERLIN — Years before the world knew Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the leader of the Civil Rights Movement, retired minister and Berlin native Rev. David Briddell called the now-iconic leader his dear friend.

Briddell, who spent 40 years as a United Methodist minister in Maryland and Pennsylvania before retiring to his place of birth in Berlin, met King while he was studying to get his doctorate degree at Boston University in the mid-1950’s. Briddell was enrolled at the university’s School of Theology. They both graduated in 1955, and perhaps ironically enough, Briddell and King were not the only ones receiving degrees from BU that day on June 5, 1955. Then senator and future president John F. Kennedy was also awarded an honorary law degree from Boston University that day. As Briddell recalls, Kennedy gave the commencement speech.

Just a few months later, King would lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, sparking what would later become a much more organized and widespread movement known as the Civil Rights Movement. From 1955 to April 4, 1968, African Americans achieved more toward genuine progress in the fight for racial equality in America than perhaps the previous 350 years combined. King is revered as perhaps America’s greatest advocate of non-violence and one of the most influential leaders in history.

Yet, for Rev. David Briddell, his perspective on everything that the Civil Rights Movement accomplished, not just for African Americans, but also for America as a whole, is admittedly viewed through a slightly different lens. For most people, King was a larger than life figure whose name lived in the headlines, his face on the televisions and his booming voice on their radios, but for Briddell, King was merely once the guy with the green Chevrolet, his own apartment, and a friend who gave him constructive criticism on his early sermons.

“None of us could have known that Martin was going to do the things that he did,” said Briddell, “but we all know he was going to do something special.”

‘The Dialectical Society’

Briddell, like many of his African American classmates at BU at the time, were very poor.

He says, during that time, racism was so bad in the south that some African American students were actually paid to get their graduate degrees at universities in the north, “just to get blacks out of the south,” Bridell recalls.

“Martin on the other hand, had his own apartment, and his own car,” he remembers, “so he would invite all of us over to his house and we would hang out like normal college students would.”

King and Briddell became fast friends, and the informal gatherings of African American classmates at King’s apartment quickly transformed into a club they called the “The Dialectical Society.”

The friends would take turns reading their college papers to one another, they would prepare meals, listen to gospel and rock-n-roll music, smoke cigarettes and talk about girls. But, many nights, those conversations took on a much more serious tone, focusing on discrimination and the issues of segregation.

Briddell remembers that when these topics came up, King’s usual penchant for humor and fun quickly snapped to the early stages of the charismatic leader that the world would later see.

“He was very passionate even then about those issues, and he really wanted to be in touch with people”, said Briddell. “We would be going to lunch and we’d walk by a barber shop and he would just go inside and start talking with people and listening to their concerns and giving them hope with his words. He would talk to anyone, anywhere: street corners, churches, and even restaurants.”

Briddell’s favorite memory of King during that time, and one that he says was a moment of foreshadowing about the man King would later become involved an off-the-cuff comment from King after he returned from a trip.

“He said, boys, I had a big funeral last weekend. We buried Jim,” Briddell said, “Someone asked ‘Jim, who?’ and Martin replied ‘Jim Crow.’”

Briddell remembers the members of the Dialectical Society all erupted in laughter at the idea of the death of Jim Crow, which was the essential slang term for segregation, because at the time, segregation was very much a firm reality in the United States.

“Looking back, Martin was able to foresee the death of that system and in announcing its death before it had actually occurred, showed us that segregation no longer had any power over him,” said Biddell.

Before The March On Washington

After graduation, Briddell says that the entire group was very surprised when King decided to lead a small Baptist church in Montgomery, Ala. rather than pursue bigger aspirations like academia or work in a much larger city like Atlanta, Georgia.

“He had a doctorate, and there were a lot of people who expected big things from him,” said Briddell, “but Martin was always a bit unpredictable. I think he went to Alabama because he already knew that he had his heart set on doing his own thing and he didn’t want to be tied down to some big entity.”

As King’s vision of civil disobedience, and organized peaceful protest took shape and became the Civil Rights Movement, Briddell became the minister of a church in Crisfield and later a church in Philadelphia.

The two friends didn’t keep in close contact, but their work made them cross paths from time to time.

Rev. David Briddell and his first wife, right, are pictured with Dr. Martin Luther King and his wife, Coretta Scott King. Submitted Photo

Yet, a short time before the now infamous Civil Rights March on Washington in 1963, Briddell helped coordinate a fundraiser for King in Philadelphia with other African American preachers in the City of Brotherly Love.

As King delivered the speech before a big crowd of people at Temple University, Briddell remembers that he noticed a change in his friend.

“He had become something much bigger than how I remembered him,” said Briddell, “something that he was born to be.”

A month later, King delivered his signature “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.

Saying Goodbye

On April 4, 1968, David Briddell was on a business trip in Atlanta when he heard the breaking news that his old friend, and Civil Rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot and killed in at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn.

“There are no words, after all these years, to describe how that felt,” said Briddell.

Stricken with grief, Briddell attempted to finish his work in Atlanta, and a few days later, while walking through the Atlanta airport, he had one last encounter with his old friend Martin.

“As I walked through the airport, a plane from Memphis arrived and Martin’s casket was taken off the plane and brought into the airport,” remembers Briddell. “It was a heartbreaking moment, but I think that moment was a gift so I could somehow say goodbye to my special friend, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.”

Still, as Reverend David Briddell looks back into that integral time in American history through a very personal lens, he says his friend was simultaneously a “once in a lifetime” kind of figure and merely just a regular guy who followed his calling and worked hard to achieve what he truly believed was right.

Briddell’s thoughts often go back to that night in the “Dialectical Society” when King predicted the death of Jim Crow. No one could have known that his friend would go on to change America and inspire millions of people, or maybe they all did in some strange way.

“He knew that it was his path, and he took that path,” said Briddell, “I’m very proud to have called him my friend.”